I was reading this blog and I am kind of love-hating it. I can't stand the extreme of the rhetoric, but I also agree with some of the core ideas. I feel the same way about this blog as I do about Jill Stein. I like the jist of it - y'know caring about children and the earth, but I really wish it wasn't so weirdly anti-vaccine and anti-science.

Parents today emphasize results over effort and learning. They discourage kids from participating in activities that "won't look good" on their college application. They hire tutors, email teachers and schedule meetings with the principal to insulate kids from ever failing. This means that our young adults are unable to deal with failure.

I like the idea of children being able to play outside and travel alone 4-8 blocks at an early age. But I don't like the complete disregard for those who live in crime-heavy environments or lack the environment safe for an unsupervised young child. Growing up with neglect and then interacting with Department of Family Services, I can see how quickly this could lead to an investigation or indicate serious neglect for the child. But that's just one example.

In the desire for strong language and decisive examples, the logic and reasonableness of her arguments just kind of... falls apart. Especially if you have recently been in the environment she describes.

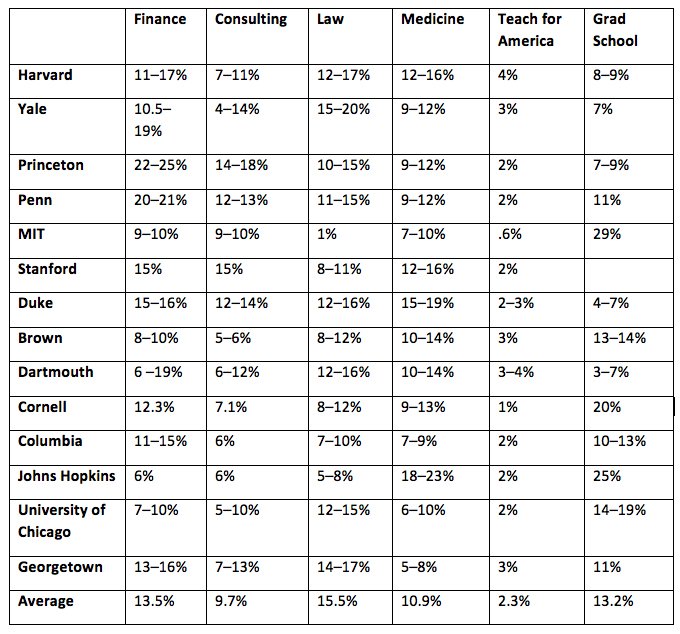

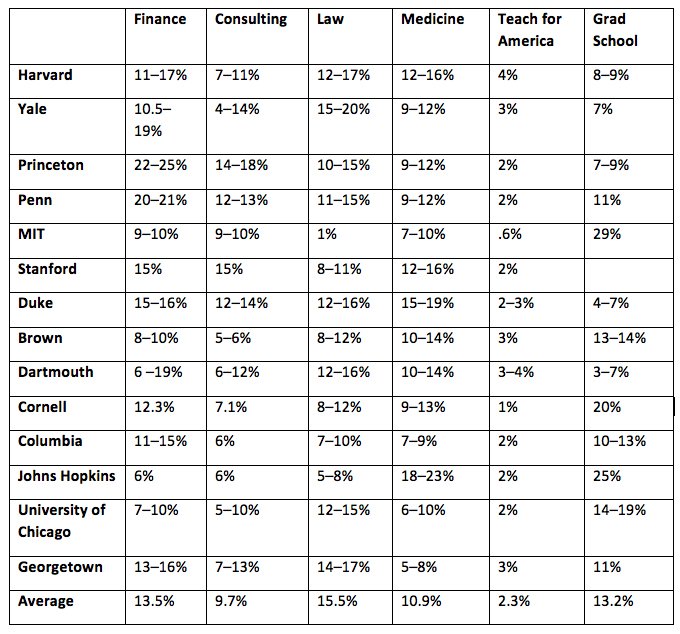

They tell their kids that studying is what it takes to get into a good college, which is what it takes to get a "good job" -- which, for over 50% of the nation's top graduates, means one of five things: med school, law school, grad school, consulting or finance.

If you've ever met a graduate student, then you probably know that this is a young person with an extreme amount of motivation and also a casual relationship with a plethora of academic fields. Some of the women I know pursuing graduate school took time to work at a start up before beginning their academic work while others have a resume of exciting travel experiences. Still more have explored dozens of career fairs and information sessions while pursuing their degree and a minor in a related field. All of the women I know in college for undergrad and graduate have pursued their interests in addition to focusing on high grades in their core curricula. Notably grad school isn't a cohesive single career, much less a pursuit that stymies independent learning. Similarly, consulting is a very broad description of careers that can cross over several fields of study. Many students from a range of fields prepare for the consulting interviews. (BTW: The questions and guestimations of consulting interviews are super fun to do drunk.) There's a lot more in this chart than just 5 dull boxes for everyone to fit into.

Pretty notable to me is the focus and idealization of start ups. Not all start ups succeed and those that do often rely on a strong foundation of privilege and economic cushion. One of my roommates spent a long time, hours and hours, into a start up. While she enjoyed the many hats she could wear while finishing her last semester at MIT, she also recognized that she was putting in far more work than she was paid for. She felt it was worth it due to the service her start up would provide if it made it to market, but we have to recognize that not all start ups make it to market and the dangers of a repeat Dot Com bubble.

Similarly, not all people enjoy start up culture. We can't all found our own company.

This sentiment seems like part of the "Do what you love" platitude that lots of college graduation speeches trot out.

DWYL, however, was the late Apple CEO Steve Jobs. In his graduation speech to the Stanford University Class of 2005, Jobs recounted the creation of Apple and inserted this reflection:

You’ve got to find what you love.

In these four sentences, the words “you” and “your” appear eight times. This focus on the individual isn’t surprising coming from Jobs, who cultivated a very specific image of himself as a worker: inspired, casual, passionate—all states agreeable with ideal romantic love [...]

“Do what you love” disguises the fact that being able to choose a career primarily for personal reward is a privilege, a sign of socioeconomic class. Even if a self-employed graphic designer had parents who could pay for art school and co-sign a lease for a slick Brooklyn apartment, she can bestow DWYL as career advice upon those covetous of her success.

I might just have had a strange cohort, but the students I knew doing the coolest things - activist or physically active - were also the ones putting in heavy hours memorizing material and getting As.

Our system of elite education manufactures young people who are smart and talented and driven, yes, but also anxious, timid, and lost, with little intellectual curiosity and a stunted sense of purpose: trapped in a bubble of privilege, heading meekly in the same direction, great at what they’re doing but with no idea why they’re doing it.

--Ivy League are over rated

Further, those of us who were most hounded by pressure from parents in high school found college to be a welcome relief. By moving across the country, we were able to set our own priorities and determine our independence for the first time. The Ivy League setting meant that our hovering parents or instilled anxieties could be satisfied with the environment and the support system entailed. In the latter half of her examples, the author admits that many of the creatives began with a stereotypical career or academic path: the tried and true background provides a fall back for the creative risk taking. And as the original article purports: young people today are strapped with anxiety as we shuffle in the same direction. But the Ivy Leagues, while bastions of privilege and ivory towers of academia, offer a green house perfected collection of the diversity of the world. With study abroad being covered by tuition and grans and international students around every dorm hall, the Ivy Leagues are actually great for prompting curiosity and adventure. If some students graduate without experiencing those moments of exploration, it seems more likely that it reflects the students and not the institution.

On the subject of institutions, both articles mention the pressure students feel. The narrow pathway to a job.

The result is a violent aversion to risk. You have no margin for error, so you avoid the possibility that you will ever make an error. Once, a student at Pomona told me that she’d love to have a chance to think about the things she’s studying, only she doesn’t have the time. I asked her if she had ever considered not trying to get an A in every class. She looked at me as if I had made an indecent suggestion.

--Ivy League are over rated

What neither article mention is that these are part of larger institutional problems. Students strapped with large debt can't think of their education as an exploration, but as investment. Ivy League schools may have larger sticker prices, but they also have more funding and garner more scholarships than state schools. Jobs are scarce, especially for new graduates and the application process becomes more intense as websites scan resumes for industry key words and interviewers expect a plethora of unpaid experience. So too do the institutions that feed into the Ivy Leagues prime us towards fear: Standardized tests aren't exactly written to be fun explorations of liberal ideas. "From learning to commodify your experiences for the application, the next step has been to seek out experiences in order to have them to commodify" -- the article does capture a bit of the background that feeds into the colleges, but I find it strange that the author at once argues that students don't seek out new experiences and believe in a pre-established sense of self and that we do seek out experiences, but only so we can navel gazing-ly write about them and develop our identities around them. It's not the week long vacation that turns into an application that riddles us with anxiety. With an increasing focus on surveillance and security in high schools and a police force that has expanded outside of urban schools into the suburbs, the constant fear and self-vigilance should be expected.

Let's turn to an example of this:

Kannokada had an engineering degree and fellowship under her belt. She had the privilege of good looks and the gut to take the risk of an acting career. But I'm sure she had the good sense to realize that very few first generation Indian women make it big in acting. So she prepared herself with a reliable and stable employment path.

We can be honest about the privileges necessary to make it at an Ivy League, but we can also be clear about the privileges built into the arguments of these critiques. Not everyone can have a Do What You Love job. Not everyone had a wonderful upbringing that makes college an easy ride or staying close to home appealing. Some parenting methods are only acceptable when enacted by a particular kind of person in a particular kind of environment.

Anyway, this article remains as conflicted as my relationship with Jill Stein. I read her speeches and find myself nodding along and irritated in equal measure. Finally, I never quite know if I'm going to write her name in or go for the standard bearing of lesser-evil.