I think we have to be very careful about how we talk about depression.

I will focus on my own experiences with depression. I will also focus on the experience of an undergraduate student at a competitive college, specifically MIT. I will include testimonies from other people, especially those of the dominant narrative that I wish to challenge.

What I have done is lay out a series of questions. I certainly hold my own answers to these questions. But I am not going to lay them out in this post

because I want

you to create your own narrative. Constantly having a narrative and explanation provided is

not my goal here.

I would like to distinguish between

talking about how we talk about depression and talking about depression itself. I am focusing on

dominant narratives. Let's define what's meant by a dominant narrative:

Dominant narratives are the stories told by the dominant culture; they define our reality and guide our lives like an invisible hand. And when the dominant culture is oppressive, so, too, are its narratives. (one green)

Dominant discourse is a way of speaking or behaving on any given topic — it is the language and actions that appear most prevalently within a given society. These behaviors and patterns of speech and writing reflect the ideologies of those who have the most power in the society. (wise geek)

There are common ways that colleges tend to talk about depression. Let's work from an MIT specific exame: I'll take a popular MIT admissions blog post paragraph and break down some ideas about depression contained within it:

“Maybe you’re depressed,” Lauren said quietly.

She told me about her depression experience—how she crawled out of the cave little by little over the past two years, yet was still in love with the Institute.

“I felt like hot shit in high school, like everyone else here did. But MIT humbled me. It challenged me physically, mentally, and emotionally. It made me more confident. And oddly enough, more spiritual,” she told me. (IHTFParadise)

- Depression as a response to something external

- Depression as an experience with a start and end

- Depression as something that makes you at better/spiritual/wise person at the end

- Depression as a quest

- Depression as an external thing that is forced on the individual

- Depression as personal, private, taboo

These dominant narratives come across in a number of ways.

Why does Lauren speak quietly? Does she fear being overheard? Is this a sacred subject that deserves quiet? Is depression a taboo subject? Is she scared to even mention depression? Is Lauren qualified to make a statement about another person's mental or emotional health? Or to make such a diagnosis?

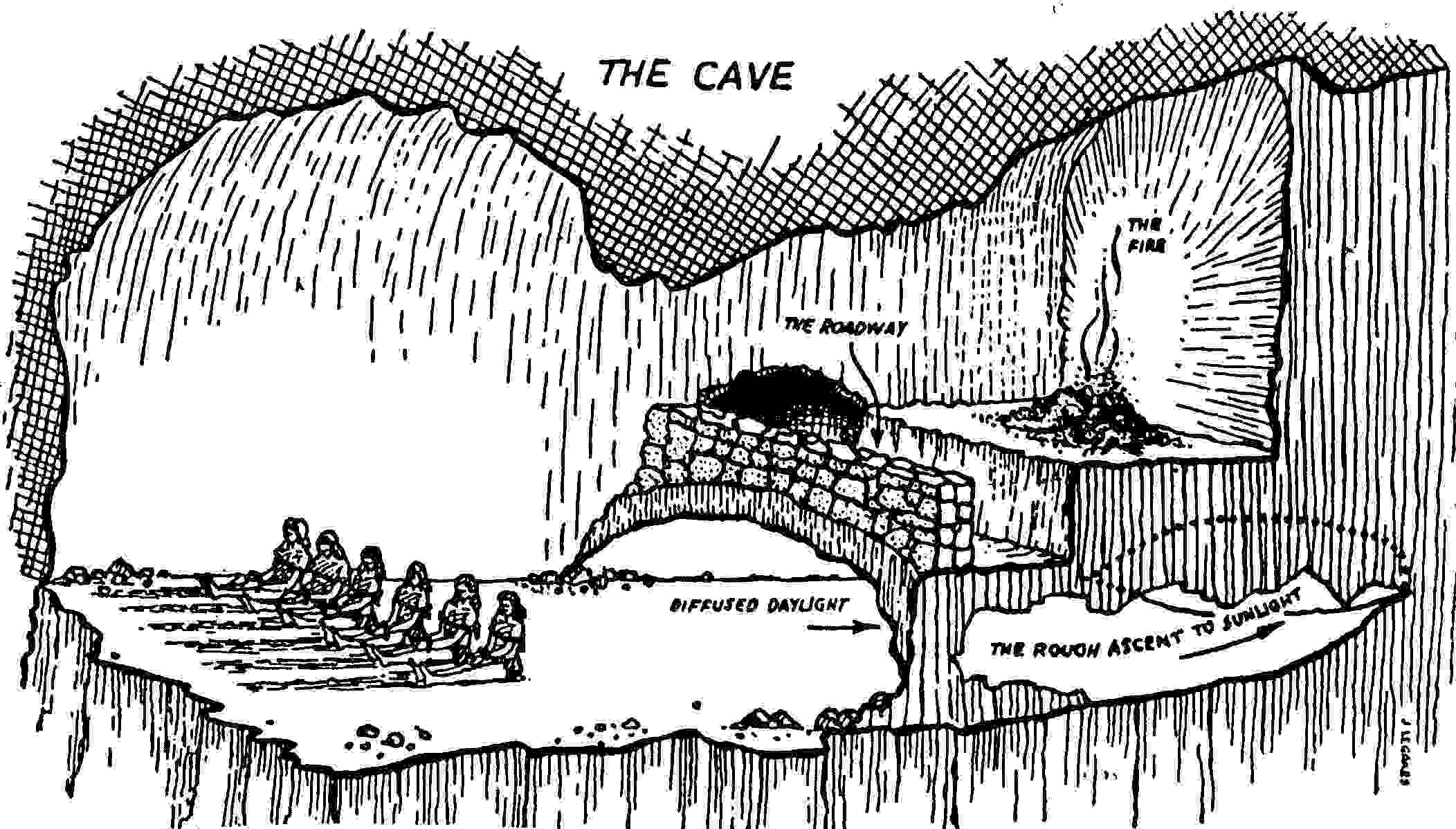

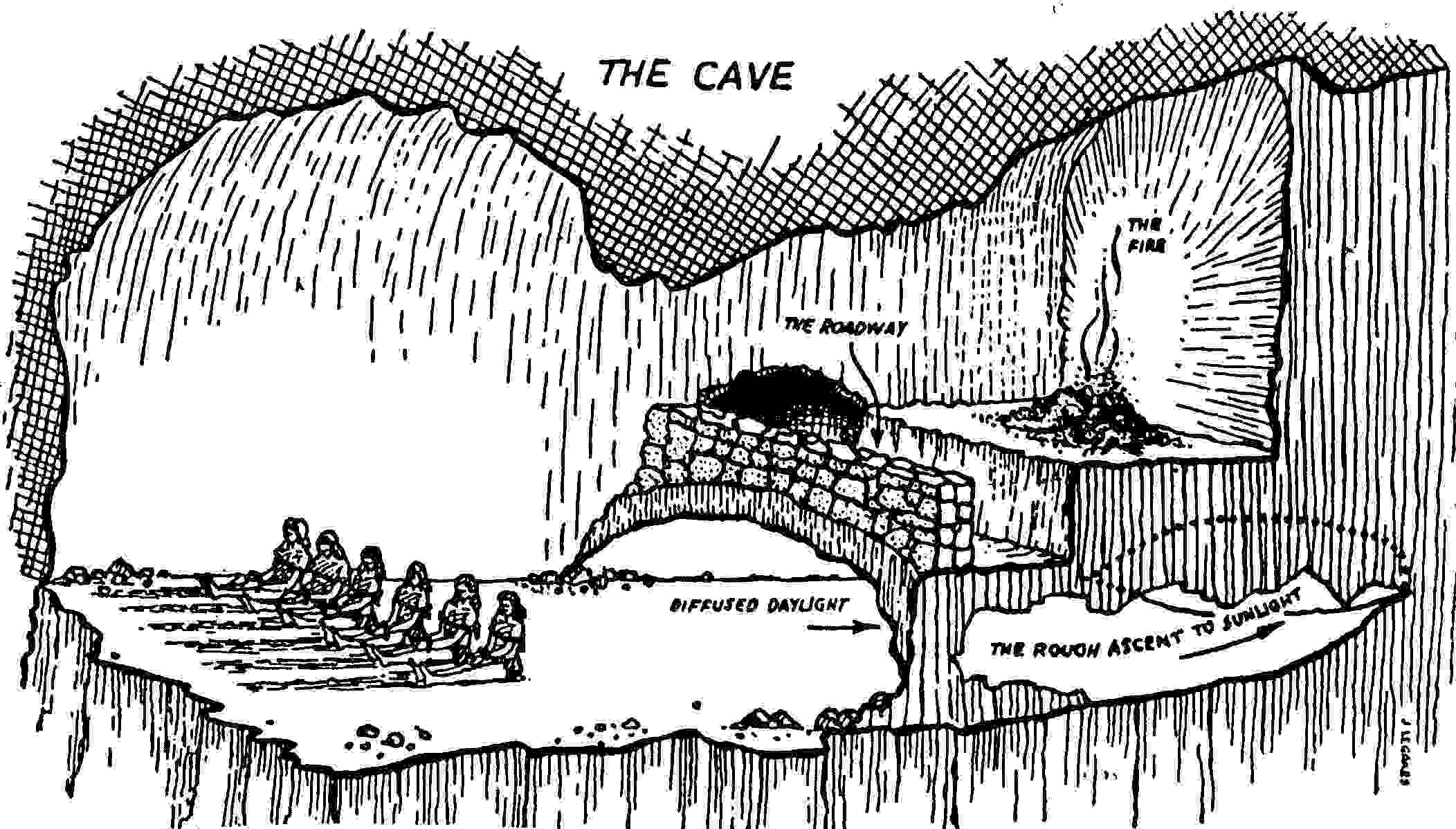

Why is depression like a cave? Is it a natural phenomena? Is it like Laurel Caverns? Is it like Plato's cave?

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="213"]

Laurel Caverns: An isolated guided tour of spiritual transformation[/caption]

[caption id="" align="alignright" width="228"]

Plato's Cave: Layers of deception and truth interacting with an individual looking for truth[/caption]

Can depression end? How do we know depression begins? How do we measure the start and stop? Who is allowed to or qualified to measure depression time?

What is a depression

experience? Is it an internal experience? Is it an external experience? Is it an objective experience? Can we call a depression experience a factual experience or true? Who can verify the experience? Do we learn from the experience? Who

participates in the experience? What qualifies the experience?

ex·pe·ri·ence

ˌikˈspirēəns/

noun

1.

practical contact with and observation of facts or events.

"he had already learned his lesson by painful experience"

synonyms: |

involvement in,participation in,contact with,acquaintance with,exposure to,observation of,awareness of,insight into

"his first experience of business" |

(google define)

And here is really the crux of my problem with how we talk about depression at MIT:

How can we love something that has hurt us?

How can we love something that has hurt us?

Should we love something that has hurt us? Can we blame the place where we were hurt?

yet was still in love with the Institute.

What is trauma bonding? Does such a term apply to student's relationship with the Institute? Can a term like 'trauma bonding' be used to describe the Institute? If so, who is responsible for causing trauma? Is the responsibility of the student to avoid bonding?

Is it ethical for the Institute to advertise a 'break and build 'em' approach to teaching?

Traumatic bonding occurs as the result of ongoing cycles of abuse in which the intermittent reinforcement of reward andpunishment creates powerful emotional bonds that are resistant to change.[1] (Wikipedia)

Intense relationships also tend to hijack all of a survivor's relating capacity. It is like a state of being burnt out. First, while it is very easy to become attached to a very chaotic and inconsistent person, it is simply not possible to form a consistent internal object representation (feeling memory) about them. (abuse and relationships)

So many students talk about burn out, the chaos of constant deadlines, the ever changing expectations:

Should we stay at a place that makes us feel depressed? Is "whatever it takes" a valid expectation to hold?

There’s a common MIT saying: Learning at MIT is like drinking out of a firehose. Classes are designed to throw too much at you. The hours given in course listings are too low for the reality of the class. Professors expect you to be able to more things than there are hours to do. Classes assume a basic knowledge that the prereqs don’t provide. Reading may not be posted until the night before they’re due. Even if the class doesn’t have a coding pre-req, basic coding skills are expected. Etc. Etc. I could go on. (MIT Culture)

Again, should we stay at a place that makes us feel depressed?

Is a firehose the only way to get wet? Would you use a firehose to water your garden? Would doing so damage the plants more than help them?

- Should MIT be allowed to make an environment that triggers anxiety on purpose?

- What if you are coming to the high anxiety set up from a traumatic or abusive background?

- Can trauma, anxiety, failure make you a better/spiritual/wise person?

- Does being SET UP for failure teach you something?

- Is an impossible quest a quest worth attempting

- Should we intend to force anxiety on an individual? Does anyone have a right to do so? What issues of consent is MIT confronting?

- How do we integrate the public MIT teaching environment with the private experience of fear?

I never hear these questions posed in the main discussion about depression. Students take for granted that they have and can consent to an experience that makes them scared and hurt. I want us to be able to challenge this assumption by first putting it out explicitly and then asking why we have accepted it implicitly.

So much the the danger in the dominant narrative around depression is that it is one of silence. I don't know how to fix this. I'm just one speaker. But I want to

believe something: MIT students can take charge of our experiences and our campus culture. Simply by changing the terms of the conversation we can create completely new ways of relating to one another and solving a dangerous issue that affects many of our friends.

When and why is it acceptable to make someone feel bad? About themselves or their capacities?

It would be normal in this state to believe that something is horribly wrong with leaving (even if it seems equally true that something is horribly wrong with staying. (abuse and relationships)

Yet despite of all these different forms, they share one thing in common—they are all facing incredible challenges while trying to keep up with MIT’s fast pace. They are some of the strongest human beings I know. (IHTFParadise)

What then does it mean when a depressed person has to leave MIT, cannot keep up with the pace? How is that person defined by our community? Are they defined by how long they stayed? By the fact they left? Whether they return or not?

Nobody slips through the cracks here. (The first step)

Really, if you have a serious difficulty, no one notices.

it’s often a herculean task of it’s own to deal unsympathetic professors

Those few resources are aimed at crisis management, not sustained assistance. (

MIT Culture)

Look at my happy summer time face with Prilla![/caption]

Look at my happy summer time face with Prilla![/caption]

Laurel Caverns: An isolated guided tour of spiritual transformation[/caption]

Laurel Caverns: An isolated guided tour of spiritual transformation[/caption] Plato's Cave: Layers of deception and truth interacting with an individual looking for truth[/caption]

Plato's Cave: Layers of deception and truth interacting with an individual looking for truth[/caption]